The Eye of Unhindered Freedom: The "Why?" and "What?" of "The Record of Going Easy"

Hongzhi and Wansong's purpose was to catalyze the awakening and post-awakening processes of people in the future - people like us.

Note: An earlier version of this post, including a Ming Dynasty introduction to the text, can be found here: On Completing the Translation of the Record of Going Easy.

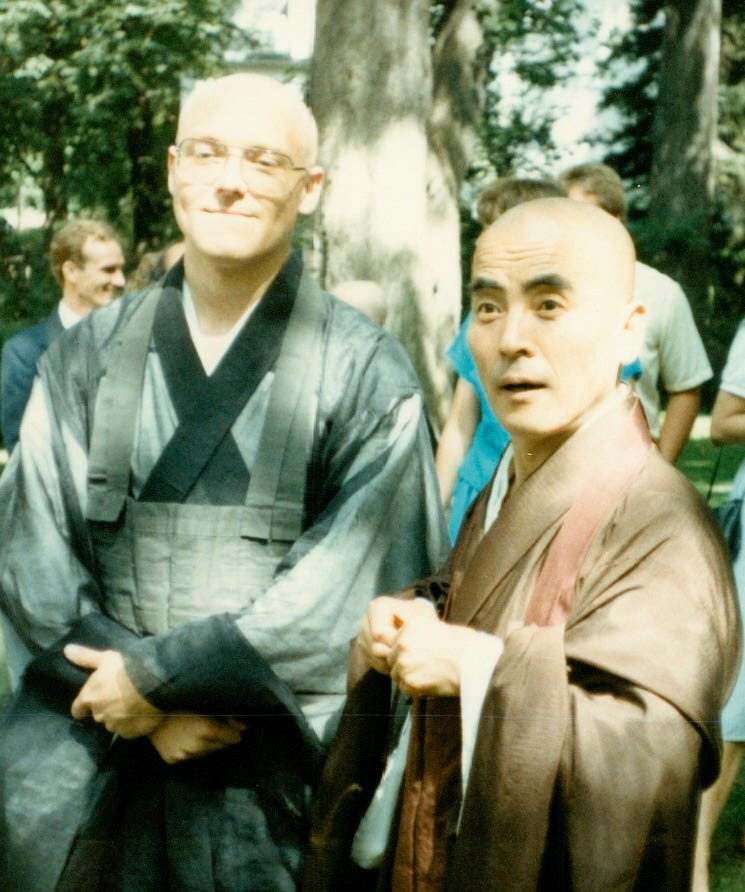

I started translating The Record of Going Easy (Japanese, Shoyoroku) ten years ago. You see, I've long felt drawn to this text, even decades back as a fairly new Zen student. And because it was the focus of my last extended conversation with my old teacher, Katagiri Roshi (1928-1990), before his death from cancer on March 1, 1990, I've long associated the text with him.

I mentioned this conversation in my Welcome video, but here I’ll share a bit more about this encounter:

At the time of this last extended conversation, Katagiri Roshi was in remission from cancer, or so we were told, and was looking forward to getting back into teaching. It was a cold January day in Minneapolis. He sat cross-legged on the living-room couch in the small apartment he shared with his wife, Tomoe Katagiri, above the Zen Center. A bright winter sun illuminated the room as we talked for several hours about many dharma-related topics, especially about several cases of Shoyoroku that he wanted me to pay close attention to, like Case 21: "Yunyan Sweeps the Ground."

At one point, we were discussing a koan involving Zhaozhou shaking out his sleeves and leaving. Roshi became particularly animated, looked at me intensely, and said "When the time comes, you must shake out your sleeves and go!"

During the conversation, Tomoe-san came into the room about every 30-minutes just to check and see if Roshi still had energy. And he did. During our talk, Roshi told me that when he recovered fully – something that his doctors told us was "100% 'likely'" – he would give talks on each of the 100 cases of Shoyoroku. However, soon after this lovely afternoon together, his cancer came roaring back. He died six weeks later.

Once I developed some rudimentary translations skills, creating a new translation of Shoyoroku began haunting me. Granted, there was already a complete translation of the Shoyoroku by Thomas Cleary (1949-2021) titled, The Book of Serenity, published in the same year Roshi died. Roshi, though, knew Thomas Cleary and had a manuscript copy of the text that he'd shared with me several years prior to publication.

One reason that I’d put off translating The Record of Going Easy is that it is huge, much larger than my other translations projects. It is also a towering achievement by genius-level Caodong (Japanese, Soto) masters Hongzhi and Wansong (more below about these two masters).

The incredible clarity of their awakenings, the vast scope of their knowledge of the buddhadharma, and the profound subtlety of their expressions was (and still is) beyond my capacity. In addition, Hongzhi's verses include many references to ancient Chinese history and Daoist teaching stories that are especially difficult to understand, let alone translate. Even Harada Sogaku Roshi (1871-1961) and Yasutani Haku'un Roshi (1885-1971) are said to have found this aspect of the text challenging.

Yet, clearly, Hongzhi and Wansong's purpose, shared across time through The Record of Going Easy, was to catalyze the awakenings and post-awakening processes of people in the future – people like us.

For a while, I piddled around with just the koans, indulging in the delight of working them from the inside (i.e., through the original Chinese characters). I followed that up by exploring various other parts of the text (i.e., introductions, verses, and capping phrases). Then about six years ago, I decided to give one full case a try, including the lengthy commentaries by Wansong. I expected that my experiment would show that the text was indeed too difficult for a dim bulb like me and I would be justified in letting the project go.

I chose Case 41: "Luopu With One Foot in the Grave," thinking that the project certainly had one foot in the grave. Fortunately and unfortunately, although translating a full case was very challenging, I was surprised that I could do it; i.e., hack my way through in such a way that these full cases might be of some benefit to Vine of Obstacles Zen students working through this later phase of the koan curriculum. So my last thread of hope for avoiding the project was severed.

The text is now provisionally completed with about 120,000 words and about 1,500 annotations. A print version would be some 800 pages. I have shared some of the early versions of these translations in the Vine of Obstacles Zen Ghost site. For example:

Stars Shining Through a Hidden Meaning: On Taking the Teaching Seat

Who were Hongzhi and Wansong?

Hongzhi (1091-1157; referred to as Tiantong in this text after the name of the monastery where he lived and taught) was a 20th-generation successor in China in the Caodong lineage. He is well-known in Zen circles today, especially due to the great works of Taigen Leighton and Guo Gu:

In terms of Hongzhi’s role in The Record of Going Easy, he compiled the 100 cases and then wrote a verse for each case.

Then about 100 years later, the introductions, commentaries, and capping phrases were written by Wansong (1166–1246; aka, Wansong Laoren, English, “Ten Thousand Pines Old Man"). Wansong was a 24th-generation successor in China in the Caodong lineage (but not directly related to Hongzhi – their last common ancestor, Furong Daokai, an 18th-generation successor in China). Given that the elements for which Wansong is responsible comprise about 90% of the text, and because Hongzhi is more well-known, in this post I'll say a bit more about Wansong.

Wansong became a monk as a kid and had his first awakening at about age 20 while working with a koan that was assigned to him by the Caodong master, Shengmo. He then went on to study with one of Shengmo's dharma siblings, Xueyan.

Xueyan assigned him the koan, "Not yet thoroughly realized," a koan much like the last in our Miscellaneous Series, "Not yet."

After Wansong worked with this koan for a good while without producing a clear response, Xueyan said, "You wait for a horn to grow from your head, until your hands and feet grow teeth and claws."

In other words, you're just messing around.

Then Xueyan struck Wansong with his staff.

The morning following this encouragement (aka, chastisement), Wansong happened to see a rooster crowing in flight and greatly awakened. Xueyan wrote the following verse in recognition of Wansong’s awakening:

At midnight a golden rooster took off crowing.

It’s not enough to rouse a secluded person from a dream.

Clouds break up as the moon, the stars, and Big Dipper quake.

Seize the great tiger, the eye of unhindered freedom.

After a few years living in a hermitage, a phase of training that’s known as “nurturing the sacred embryo,” Wansong went on to have a long and successful career as a Zen master, despite the extraordinarily difficult political developments of his time (like China being conquered by the Mongols). He produced a handful of important Zen texts and transmitted to at least a half-dozen dharma heirs. His students included Kublai Khan and Prime Minister Yelu. Yelu, a householder, also became one of his dharma heirs. And Wansong's lineage continues today through the Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association.

You can learn more about Wansong in the introduction to Going Through the Mystery's One Hundred Questions.

In The Record of Going Easy, Hongzhi and Wansong demonstrate a fluency with the buddhadharma that is characteristic of the ancient masters, but rare today. Hongzhi and Wansong were not only brilliant, they devoted themselves full-time to the buddhadharma – also rare today – and both possessed an astonishing breadth of knowledge.

For example, Wansong cites about 250 different masters (25% of whom I failed to track down – they seem to be near contemporaries of Wansong and so too late for entries in The Record of the Transmission of the Lamp and similar texts). These masters represent an equal balance between his own Caodong line and those of Linji, Deshan, and Guishan. In addition, in case after case, Hongzhi and Wansong surprised me with their vibrantly fresh and creative expressions.

Truly, this is a text that offers a clear and strong voice of One School Zen. Hongzhi and Wansong's voices boom in harmony with the voices of hundreds of other Zen masters in such a way that it's difficult to discern who's on first.

Why translate a text that's already been translated?

Especially since I translated Going Through the Mystery's One Hundred Questions, it's been apparent that Cleary wasn't always so clear and didn't feel the same tone in Wansong's commentary as I do. Cleary makes Wansong sound baroque and abstract, as if his energy was directed vertically into the great beyond. As I worked with the Chinese characters, I saw that Wansong was earthy and funny, with energy that was horizontal – more all-embracing than transcendental.

Moreover, for students engaged in working through The Record of Going Easy's 100 koans as part of the Harada-Yasutani koan curriculum, the Cleary translation (as well as others I'm aware of) tends to obscure the koan points rather than render the Chinese so that the koan points stand out in relief in English.

Cleary also hides technical terms, so much so that most Zen students probably aren't aware of connections between the teaching of Wansong and the essential teachings of buddhadharma. For example, Wansong uses the term "diligent effort" (功夫, Japanese, kufu) eleven times in the text. I bet even those who are really familiar with Cleary's Book of Serenity hadn't noticed. Cleary translates 功夫 variously as "effect," "effort," "work," "method," etc.

So throughout my translation, I aim for a consistent rendering of key terms, hopefully, knitting together a tapestry of buddhadharma. Many of the footnotes unpack these key terms by sharing more about what's being implied in the text by the use of that particular term, like "diligent effort." Many of the footnotes are also devoted to identifying the vast cast of characters that appears in the text and aim to concisely identify their lineage and generation, highlighting the "One School" emphasis of the text.

Thank you for reading.

Coming soon:

Examine! Look! Case 1: The World-Honored One Ascends the Seat

Opening the World: A Conversation with James Myoun Ford Roshi